|

We’re so excited to announce that “HRO: Adventures of a Humanoid Resources Officer” has been chosen to appear in this year’s Boston Festival of Independent Games. This online community event will run Saturday, May 20, through Sunday, May 21, 9AM-5PM ET. Stop by our virtual booth during the “showcase” hours on Saturday (noon-5PM ET) and chat us up about game development or HRO and play a demo with us! Tickets are free and available here on Eventbrite. And speaking of this weekend — HRO will be releasing on Steam this Sunday, May 21! We’re so excited. Hope you are, too.

0 Comments

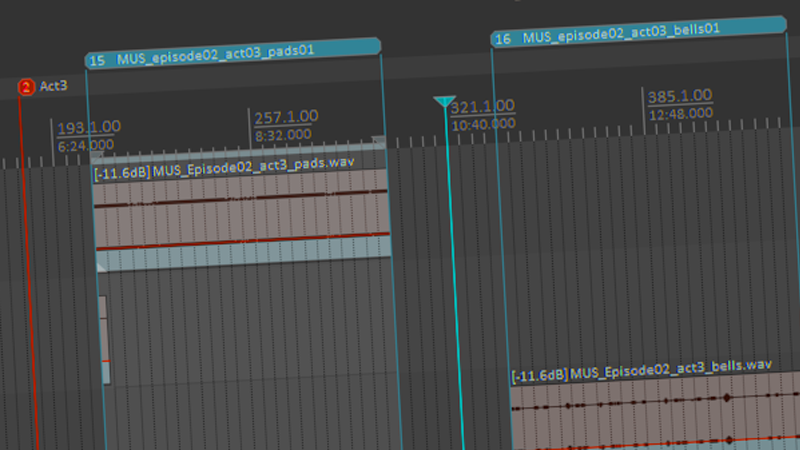

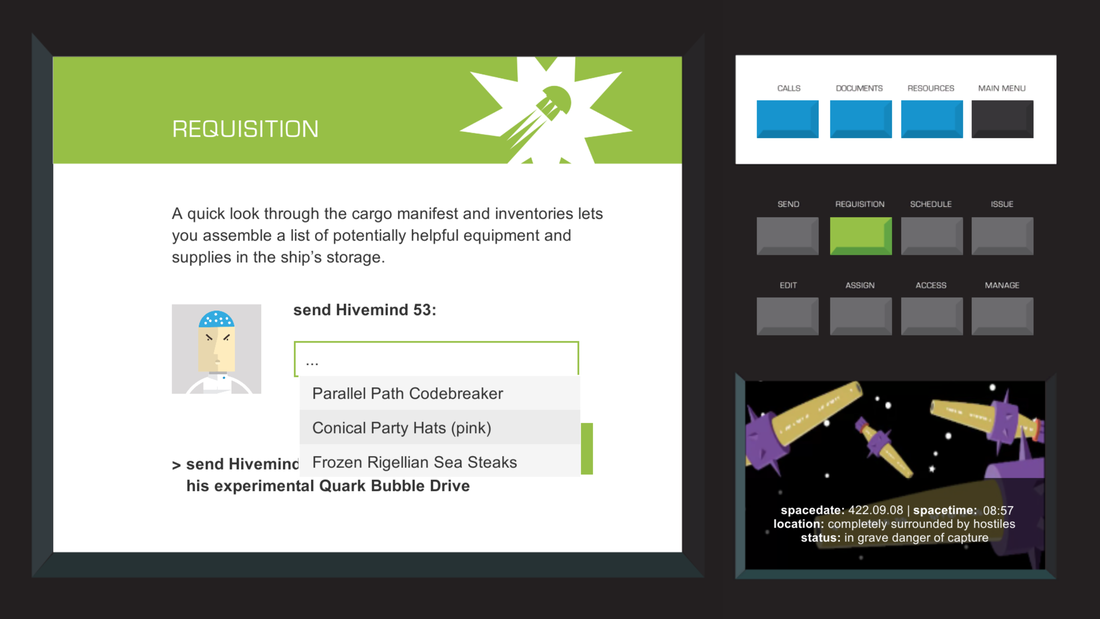

Back in the day, games were shipped to physical stores. On floppy disks or CDs. In a box. And if you were really lucky the box would also contain stuff. In the industry they’re referred to as “feelies” and they were things like maps and notebooks, or — in one particularly memorable instance — a set of cardboard glasses attached to a plastic pig snout. Of course, we’re distributing HRO: Adventures of a Humanoid Resources Officer via an online merchant, but we wanted to try to capture some of that world-building excitement we felt when we opened video game boxes in the eighties and nineties. So we produced a limited run of physical boxes, complete with an HRO “Orientation Guide” and your very own CSS Endeavor crew ID lanyard. There’s also a link to a special microsite where you can create your own custom crew avatar and identity card to print out. (You can check out the microsite at tinyurl.com/2p8zwhb8 ) So if you do happen to see us at an in-person festival or conference, stop by the booth and we’ll have some copies to show off. In the meantime, stay tuned for the release of the game on May 21! We’re so close! Before I started working on video games I was a writer and a performer — and I’ve always had a fascination with comedy. How it works. How it’s structured. How to get the unexpected laugh. That sort of thing. One of my favorite comedic devices is the callback. A callback is a joke that works because it refers to an idea or event that happened earlier in the same script, or — more commonly today — an idea or event that came up in an earlier episode or season of a show, or in a previous film in a series. The joy is in the connection. The audience gets to put the pieces together in real time and feel the thrill of making the association (“I’m wicked smart to get that!”) and the thrill of sharing the inside joke (“the writers were wicked smart to put that Easter egg in for the loyal fans!”). A well-crafted callback can also add to an audience’s sense that the fictional world is vast, living and persistent. One of my favorite examples of this is in Dan Harmon’s Community where a character notes that fire can’t go through doors because it’s not a ghost and then — half a season later — a different character remarks on how ghosts can’t go through doors because they’re not fire. Neither joke is a particular gem alone. Together they’re gold. There are a couple of different styles of callback in HRO: Adventures of a Humanoid Resources Officer. The most obvious is in the conversations the player has with various characters. They’ll remember your responses and refer to them later in the interaction, and you’ll sometimes be given unique response options based on what you decided to say earlier. There are also several running storylines that play out only in your inbox messages as the game progresses. And, of course, there are inbox messages which are callbacks to conversations the player has had or events that they instigated in the course of play (I will only say the word “hamster” here). We hope you enjoy them as much as we enjoyed building them. HRO’s development cycle is coming to a rapid close — release date is May 21! We’re so excited to share this with all of you. We’re breaking with our blogging tradition this time and welcoming Worthing & Moncrieff’s resident sound designer, Eric Hamel, to talk about composing the score for HRO and how he sees the role of music in the larger development context. So if this post is mysteriously more coherent and less snarky than our usual fare, you know who to blame… Music has long been an integral part of the gaming experience. It’s an essential tool for immersing players into the game world, enhancing action, and shaping the emotional tone. But composing game music is uniquely challenging because the player has control over the action and events the score is intended to complement. When composers score a film, they know exactly when events take place and how the action will change. Game composers don’t have that same luxury of predictability. On a practical level, structuring the music in HRO has been an exercise in balance. As an interactive narrative experience, I was looking to strike the right balance of melody so that character themes could be explored — without creating a distraction for players reading dialogue or working through a puzzle. And there’s a lot of dialogue in HRO (like, a lot). To avoid listener fatigue and hit that elusive sweet balanced spot, I used a system of pattern and variation. In our three act system, most episodes conform to a pattern whereby the first two acts have a similar atmospheric track that changes based on what the player is doing. If the player is having a conversation with a character, we’ll hear a familiar chord progression. But if the player is digging through resources or exploring an action panel, the chord progression will complicate. In the third act — the height of the narrative tension — we hear a more orchestrated version of the same musical idea. However, instead of the chord progression changing, the instrumentation changes based on the player’s activity. This concept was extended to the potential game outcomes. If the player is exploring an administrative action panel that is sure to lead the Endeavor to certain doom, they’ll hear more foreboding instrumentation. The bassline, for example, might become more prominent. Alternatively, if the player is exploring an action panel that can lead to success, they’ll hear instrumentation that’s more triumphant and heroic. Horns might become more noticeable, or the episode melody might take over. Most players won’t be conscious of the specific messaging in the scoring, but their experience will be affected and perhaps even gently guided by the cueing — on some level. A game audience has agency — and by directly harnessing the power and unpredictability of that agency to the score itself, I’m aiming to integrate the music and the core game mechanic to create a more immersive and impactful experience. When the music is connected — in a meaningful way — to something the player chooses, it ceases to be background and gains the potential to connect on a deeper emotional level. This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity. MARC: This is the blog post where the developers of HRO talk about our favorite characters in the game. And I thought it might be interesting for us to say who our favorite recurring character is and who our favorite “guest star” is. ERIC: Love it. Yes. MARC: So my favorite recurring character — this will hardly be a shocker — is the science officer. Commander Kondor. <in the accompanying graphic, Kondor is on the far right> Just a little background, Stella Kondor is a Chirchirroid, which is one of the alien races in HRO. They are famous as the sticklers of the galaxy — the rules followers and the referees and they’re the people who point and say “six items or fewer in the express checkout line!” ERIC: And they’re very unpopular as a result. MARC: But that is like, definitely, totally me. I really dig the whole “let’s have rules and let’s all follow them” thing. So I have a soft spot for her. Everybody in the crew also dislikes her for that dedication to order. There’s a lot of pushback about how she’s too much “by the book” and won’t bend the rules — like to give Dr. Singh the scans of the planet so she can tell if her daughter’s still alive on Kirmulis Majoris. And Kondor just won’t do it. No! No, that’s the rule! ERIC: That’s very Kondor. MARC: And I love that we later find out she has a very adventurous love life. Which is a beautiful combination of contradictions, right? She’s like this uptight paragon who is also an unapologetically equal-opportunity romantic. Plus the voiceover work is beautiful. ERIC: Liz’s audition was a real surprise! MARC: Totally! Right out of the box and I was like, “Oh! There she is! There’s Kondor.” ERIC: So my favorite recurring character? I might surprise you, but I think my favorite character is Lieutenant Whitford. <far left in the illustration> MARC: Why would that surprise me? ERIC: I don’t know. I think he’s very funny. He’s so oblivious! He’s got a heart of gold but he’s completely oblivious to everything going on around him. Right? He sort of feels like everybody’s little brother that needs protecting. MARC: Right. ERIC: He entertains me in that way. I go back to his conversations and there’s always something that makes me laugh out loud. MARC: It’s funny because of his lack of self knowledge, but also his lack of competence. When you pair those two things together… ERIC: I don’t know about that. I’m gonna push back on that because I mean, he’s reasonably competent as a navigator. I think. Right? MARC: Well, the one actual navigational problem in the game was not actually his fault. ERIC: Yes. I feel like — as a navigator — he’s very competent. All the mistakes that we see him make — and we do see him make a lot of mistakes — are all security and password problems, personal problems, things like that. MARC: And I think it’s suggested that he’s responsible for the genocide of an alien species. ERIC: Well, partially responsible, but I mean, like, yeah, he has zero life skills. But navigationally he’s competent. <laughter> MARC: Another interesting thing about Whitford is the distance between the player’s relationship with Whitford and what Whitford thinks their relationship is. It’s the biggest disconnect of any of the characters you talk to. ERIC: That leads to some interesting exchanges because he seems to think the player is his best friend. Which I also find very endearing. Especially in that unlockable episode when Mr. Whitford -- MARC: — D. Carole. ERIC: Right. Do we ever find out what the D. stands for? MARC: I think his sister tells us if you ask her the right way. ERIC: Right, OK — so I love that unlockable scene where D. Carole Whitford defends the player when the other junior officer start bad-mouthing them. MARC: Oh, Mr. Whitford… OK — So who do we love for guest stars? ERIC: My favorite guest star is Dr. Callis. <second from the left in the image> MARC: Oh, really? ERIC: That’s a surprise? MARC: Only because I’m going to bookend your choice — my favorite is Jakulis Spitz. <pictured third from the left> For those of you who are following this conversation on the blog — that’s a thing because those two stories are mutually exclusive. So if you meet Dr. Callis, you would never meet Spitz. ERIC: Right. MARC: And why do you love Dr. Callis? She has a boss hairstyle — I’ll give you that. ERIC: She has style. Yeah, there’s no question about it. But also, the episode Dr. Callis stars in is a great exploration of obsession. She has such a commitment to her life’s work. I mean, she’s willing to put everything on the line to get what she needs — no matter the cost. MARC: So I feel the same way about Spitz, the criminally-insane cult-leader. ERIC: Also a character who is obsessed. MARC: But that’s not why I love him. I love Spitz because he is such a beautiful example of redemption. What he has that Dr. Callis doesn’t is that Spitz can make the single biggest turnaround —the most radical change of heart — of any character in the game. ERIC: Does he always redeem himself? MARC: Not always, but it’s possible. ERIC: But it doesn’t end well for him. Actually it doesn’t end well for Dr. Callis either. MARC: Well, it’s obsession. When does obsession ever end well? ERIC: Right. But I guess I identify with that. In both Spitz and Dr. Callis. MARC: Dr. Callis is putting everything on the line — which is how you characterized it earlier — and I agree. She’s putting everything on the line. But she’s also putting everybody else’s everything on the line. ERIC: Well, that’s the heart of obsession, right? MARC: He says, obsessively. <laughter> ERIC: Picking favorite characters wasn’t so easy! I mean, I was very close to choosing Hivemind 53. MARC: Also a great choice. I love them. ERIC: They bring a unique perspective to the game — as a group of intelligences inhabiting a single body — but I felt like they didn’t have enough screen time to count as a major character. MARC: I felt the same way about Nurse Williams. As a character he makes some interesting choices. I also like the fact that he’s a poet. So I enjoyed writing for him, particularly, because his cadence and word choices are so specific. But again, I thought he wasn’t enough of a presence to be considered, you know, part of the main cast. ERIC: So we can file those under “Honorable Mention.” MARC: So thanks, Eric. I know it wasn’t easy to pick favorites with, what? Forty-plus characters in the game. ERIC: My pleasure. I hope the readers enjoy the conversation. So this week is PAX East here in Boston! As part of the week-long festivities, Worthing & Moncrieff will be showing off HRO: Adventures of a Humanoid Resources Officer at the Made In MA at PAX East 2023 Party on March 23rd. We’re really excited to get the current build in front of players and to connect with our local friends and colleagues. So if you’re in Boston for the big show, we hope you’ll come by, have a drink with us and play some games.

We’re also pleased to announce that W&M’s own Eric Hamel will be participating in a PAX East panel on voiceover best practices. Check out their website for more details. There’s a terrific episode of Will & Grace in which Jack is so wrapped up in his acting career that he doesn’t notice his best friend Karen’s life is falling apart. A few dozen punchlines and one really amazing epiphany scene later Jack course corrects. For me, this is a perfect metaphor for playtesting. It’s a scheduled period for me and Eric to stop, step back, and listen to what our players are saying. At W&M we’re big believers in the power of playtesting to identify problems. We’ve found that when a player finds a problem they’re always right — there is always a problem. How that problem gets resolved falls to the dev team. The key is figuring out why the player was prompted to say what they said. The right fix requires us to balance the original vision for the game, the technical constraints we’re working under, and the larger game experience as a whole. Perfect solutions are sometimes hard to come by — but we take our commitment to crafting the best possible product very seriously. Feedback is absolute gold and we want to thank all our playtesters for their time and keen insight. HRO is coming out of Beta testing today and we’re looking forward to assessing their comments and making a plan to address the questions that the process raises — all with an eye toward our upcoming May 23 release date! Very exciting! We’ve been working hard on HRO even if we haven’t been talking about it much. So here’s a few things we’ve been thinking about and implementing over the last six months or so: The main way players affect the HRO universe is by doing bureaucratic stuff — we call them “actions” — including things like requisitioning exotic equipment, assigning crewmembers to specific roles and tweaking the meeting snack budget. A lot of time recently went into creating all the permutations. The game has about 215 distinct administrative actions a player can take across the sweep of the game. Getting them all to work mechanically and getting them all to work narratively within the framework of their stories was kind of a bear. When we started this project we were committed to the idea that a player’s choices should have consequences. Because of actions a player takes, characters in HRO can die, careers can be made or ruined, and Kirmulak secret agents can be exposed. There are also six mini-episodes unlocked by specific player choices. In order to manage all this potential variation, Eric put together a nifty “flag” system to keep track of and trigger variations. Which gives us the opportunity to do big things like swap in alternate cinematics or conversations if a featured character is no longer available — and small detailed things like swap in alternate email messages in the player’s inbox to reflect the particular path they’re taking through the game. And, of course, getting the full playable version on its feet has been a huge help — finally we were able to evaluate the flow of the game and examine the story connections in real time. A lot of mechanical questions got answered, and a few new ones got posed. We’ll be talking amore about this issue in the next post where we tackle the playtesting and the process of evaluating and acting on feedback. Stay tuned. We are just about to enter one of my favorite phases of the development process —beta testing! Yay! We’ve been working hard and HRO is, officially, feature complete. So now it’s time to hand it over to friends and generous volunteers to “stress test” our baby. This will be the first time anyone outside the W&M team will be able to play the entire game through and we’re really looking forward to the player feedback. In an ideal world, we would be playtesting the game at a show or festival in addition to distributing keys for people to play on their own time in their own homes. The advantage to the in-preson festival-type testing is that the feedback is immediate. We can see how far a player gets, where they laugh, where they get stuck and we can learn a lot from the questions they ask. Our playtesting philosophy is to be as hands-off as possible and just watch players play. It’s observational. We get to be Jane Goodall — you know, if Jane Goodall studied video games instead of gorillas. Of course, in-person game gatherings have been kind of rare lately. Which means this month of beta testing for HRO will be remote — with players playing on their own at their own pace and filling out a questionnaire with their comments and reactions. We don’t necessarily capture as much experiential data as we might at an in-person event, but the players get to spend more time with the game. And they get to send along more detailed reactions and comments. If you’d like to participate in the beta, please drop us a line at [email protected] and we’ll see if we can get you on the list. It’s our great pleasure to announce that our retro sci-fi visual novel has an official Steam release date! HRO: Adventures of a Humanoid Resources Officer is currently slated to release on May 21, 2023. Yay! We couldn’t be more excited to share this with you. All of us here at Worthing & Moncrieff are grateful for the help and talent of so many fine collaborators — and for all the stuff we learned along the way! Boy, this one really stretched our horizons. But the finish line is in sight and the game is in great shape. Stay tuned for more news as the big day approaches. |

AUTHORWorthing and Moncrieff, LLC is an independent developer of video game stories founded in 2015. ARCHIVES

December 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed